Bruno Martinazzi. Journey Into The Soul

Author:

Petra Hölscher

min

Reading Time

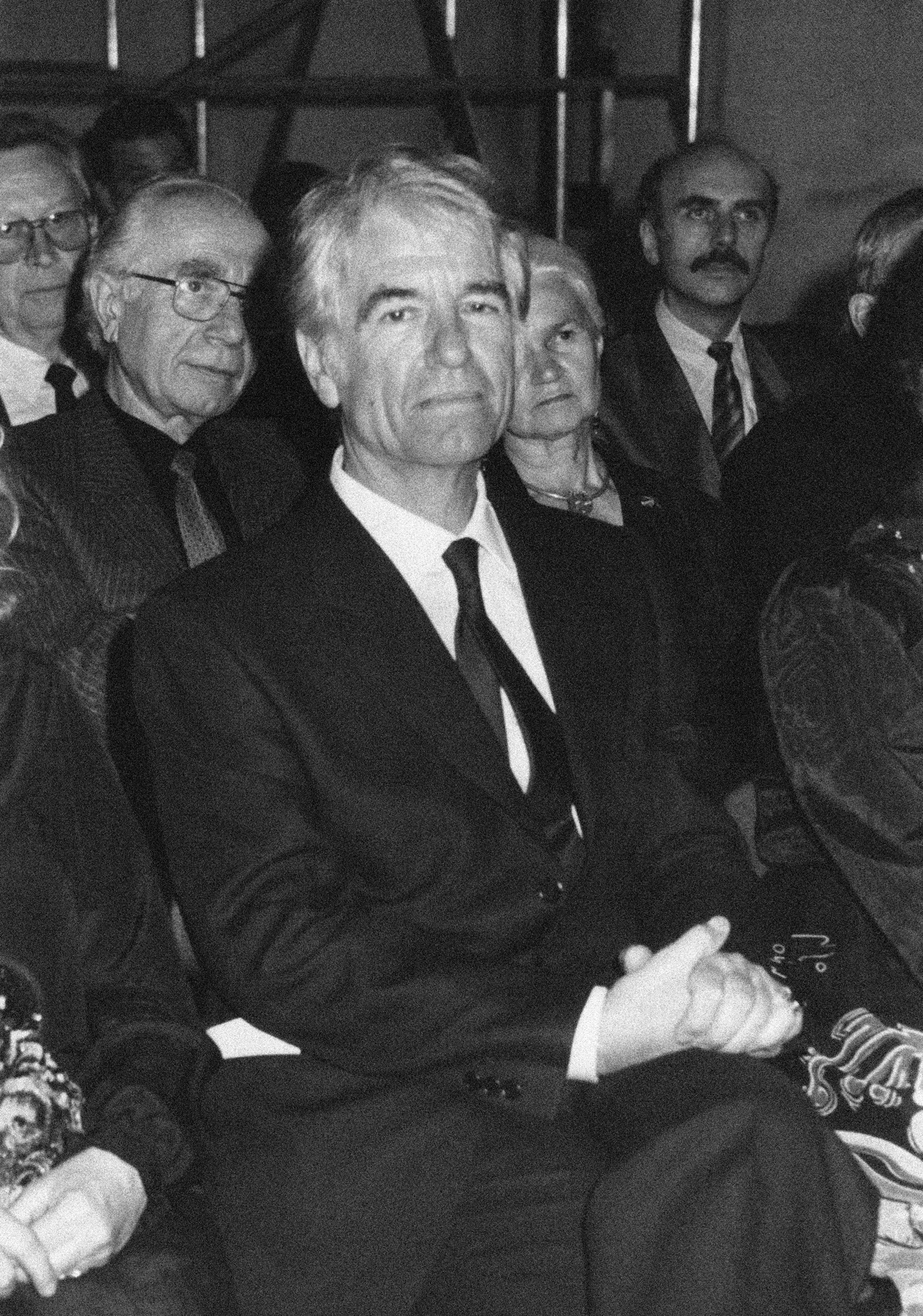

Bruno Martinazzi was born 1923 in Turin. One of the greatest names in studio jewelry died on July 14, 2018. Munich was an important station in his life as a jewelry artist.

The Italian grand seigneur was linked with the Bavarian metropolis by friendship with the goldsmith and academy professor Hermann Jünger (1928-2005) and by collaboration with Herbert Hofmann and his successor Peter Nickel. Both were responsible for the jewelry exhibition at the Internationale Handwerksmesse, which has taken place annually since 1959.

Martinazzi was honored with the Bavarian State Award in Munich in 1965, followed by conferral of the Golden Ring of Honor of the Society for Goldsmith’s Art in Hanau in 1987. Martinazzi, whose predominantly gold jewelry objects outstandingly embodied Italianità, accompanied the work of Die Neue Sammlung and the Danner Foundation with very great and friendly interest. One of the high points was a collaborative exhibition in 2011 entitled “Bruno Martinazzi. Memory Maps”:

Several years previously, Bruno Martinazzi had accepted Die Neue Sammlung’s invitation to give a lecture in the „All Abaout Me“ series at the Pinakothek der Moderne in 2005. In that talk, he described the path that led him to become a unique artist whose widely admired creations exerted an essential effect on the evolution of studio jewelry around the world.

From the vantage point of Die Neue Sammlung, and now that Bruno Martinazzi has reached the end of his way, it seems appropriate to reprint abridged excerpts from his lecture:

(…)

In my childhood I tried to do the same things that my father had done so passionately. My mother told me that my father had loved mountains and photography. I played with the chemicals and his development equipment in what was rather an unprofessional dark room and watched as fairy-tale mountains appeared. (…) Mountain climbing became a passion. In 1947, after four years of absence due to the war, I returned to the mountains.

(…)

There is a time that destroys and a time that saves. I believe that time leaves us a gift but it is up to us to recognise this and to know how to protect our things: this gift is the ‘soul’. The things that are absent gather in the soul: all that we are forced to separate from, our wishes and everything that has no place in reality. I try to understand myself and others but, in order to do so, I need my hands and my body, just as in mountain climbing. I know that I cannot attain perfection and beauty but I can work in beauty, I can strive for beauty and make art. At the age of ten I took violin lessons. My teacher wanted me to devote myself in music. My family was against it and I studied chemistry right through to the diploma. When I was thirty years old, I finally began on art but it was too late for music.

(…)

‘Matter yearns for form just as the sick person longs for health’, thus spoke Master Eckhart, a famous German mystic. Stone and gold wait patiently: gold is imperishable and it is as if stone takes on a soul with time. ‘There are stones that warm like hearts and hearts that are as cold as stone’ (Talmud). The forms that await liberation are in the souls of poets and therefore, of all people. In a poem Giacomo Leopardi deals with some of the most weighty subjects: infinity, life, death. However, they are handled with a light touch and so graceful are his words that they make heavy things light and light things heavy. I try to give birth from beauty to the art to which I am committed. I mean the beauty of classical antiquity, which I have inherited from those who before me drew their knowledge from it. One must safeguard this knowledge from negligence and foolishness. Recent research has shown that a considerable part of the brain controls hand movements. Embossing a little piece of sheet-gold or sculpting stone are activities that are the exact opposite of each other, mirror-images of one another, or, if you prefer, games: the hammer enlarges the sheet of gold; the chisel reduces the size of a block of stone. Tools of varying sizes together with points and hammers of different weights and differing shape are used. There is, apparently, continuity but the games are indeed different. The sculptor works outdoors, in the natural environment, often together with other people. The goldsmith works alone in an enclosed space, concentrating on a small object which is built with the aid of fire. Sculpting is encounter/embrace; gold requires fingers that are both powerful and delicate. In sculpture form and strength are revealed by the time the work has almost been finished whereas in goldsmithing, the form immediately comes to light; it is, however, at the very beginning extremely fragile and must be nurtured and strengthened. The scuptor can, in a certain sense, be compared to a titan; the goldsmith is part alchemist and part shaman. The alchemist observes, investigates and tests matter; his means are water, fire, myths and philosophy. The shaman acquires his knowledge from indeterminate forms. Making art means learning and knowing. Making something and creating with body and soul helps one to unterstand reality. What we call art is ‘that ancient connection of soul, eye and hand.’

‘Man can know himself as the core of doing and of contemplation, of the hands and reason’ (Giordano Bruno, Lo Spaccio della Bestia Trionfante). The year 1968 was the year of student protest. I was teaching in Savona. It was like a shock-wave, a desire for change. In my work it was also a turning-point for me. Expectations were soon disappointed; consequently, my perception of the world also changed; the tidal-wave receded, leaving behind the fragments of a destroyed reality. When I at first observed these fragments with irony, I feel increasingly tempted to redeem them, to put them together again into a whole picture. However, not the last fragments but units striving for wholeness.

(…)

(…)

In ancient Greek there is a word, THUMŌS, which from Homer onwards has had a great many meanings. It can be translated as ‘yearning’, ‘breath of life’, ‘the effluvium of the soul’; perhaps the German word ‘Streben’ (striving) expresses this meaning. Ovid’s poem ‘Metamorphoses’ has always provided poets and artists in Italy, where one very often borrows from myth, with an inexhaustible source of metaphors. Myth is oral history, narrative, knowledge before the logos. Here myth is not the form that gathers or where our thoughts lie. Here the artist uses myth to lend strength to his thoughts. The artist does not withdraw into nostalgia; he strides with his power into the present life, the moment in which form is born.

For me, America was the land of Stardust, Flash Gordon, Jean Harlow and Wallace Beery. The rays of freedom no longer radiate the light I once thought they did. The mouth is constantly changing in form and meaning. Now a blade has cleft it into two; its beauty is deeply wounded. However, violence cannot destroy its dignity; its lost beauty has not been extinguished.

The concept of chaos / injury becomes the concept of chaos / opening. On the one hand, the split signifies that wholeness has been lost; on the other, lift can be born of that opening. In mythology, at the very beginning was chaos, which generated the Earth. This concept of wounding recurs in the works on Narcissus. Narcissus, too, reveals a split. This injury cannot be healed. Narcissus is separated from his mirror-image by the mirror; he wants to appropriate this instead of attaining knowledge through it. Knowledge originally revealed itself with joy. Instead of loving beauty, Narcissus wants to possess it but one can only touch, question, fear, learn beauty: ‘Truth is beauty and beauty is truth’. The mirror reflects what is behind the viewer. What is behind us is already in the past, something to reflect upon, but life is what was seen before our eyes. The mirror reflects the past, there is no life. Narcissus succumbs to temptation and steps into a deadly trap and is lost. Narcissus is turned into a flower and loses his body.

(…)

Love … each of us has experience that could be told. What is a kiss? A promise? To evoke the ineffable? What is love? Dante writes in the Divine Comedy, Purgatory, 18th Canto, verse 25: ‘if she, thus drawn, / Incline toward it; love is the inclining….’ A very slight stirring of the soul, that is the origin of a flame, that ‘… ‘ne’er rests / Before enjoyment of the thing it loves.’ And again Dante tells us that the highest expression of love consists of comprehending the good. Hölderlin says: ‘It is from joy that you must understand what is pure’ (Aus Freude musst Du das Reine überhaupt verstehen) and speaks of ‘enduring what is momentarily incomplete’ (das augenblicklich Unvollständige ertragen).

(…) Myth, religion and philosophy (…) become reflections of the soul, monograms of the ‘One’, the ‘Hidden God’. These are triads: the heart of Heaven, a myth from the Quiché kingdom (now Guatemala). The Greek triads of gods of medicine: Aesculapius, Hygieia, Telesphorus (the child-god) who, together, protect us from disease. The attempt to summarise the essence of a thought by means of an abbreviation. In his work ‘Erga kai Himera’ (Works and Days), Hesiod writes that men were created similar to the gods. This was called the Golden Age. In that age the decline of man towards evil and suffering began. Raimondo Lullo, poet, alchemist and mystic from Catalonia, wrote in his ‘Ars Brevis’ around 1300: ‘Man is an animal that becomes a human being“. The classic poets set what they envisaged as the future in a mythological past. I would interpret Hesiod’s myth entirely differently: unlike him, the Golden Age, Paradise Lost, are only metaphors intended to express man’s hightes, arcane striving.

(…)

Gold has led me on a journey into the soul; my dialogue with stone has led me to feel as though I touch time. While I was working, I wondered: why is stone so heavy? The stone on which I was working came from a mountain, from a landscape dotted with rhododendrons and bilberry shrubs. And even earlier, millions of years ago, this stone was already there as I was able to ascertain from my geological maps. I gradually conceived a symbolic weight / time equation, as I have represented in my work ‘Matter and Time’.

I compared our familiar, certain units of measurement with the units of measurement of matter, which can be measured in millions of years. It is a mind-boggling magnitude, beyond comprehension – it is infinite magnitude. And yet, while I was working, it was as if I might be able to touch this infinity, that eternity. Time and the beauty of matter, contained in the simple forms weight, matre, a vessel, an inch. An unsettling retreat of ego.

(…)

The hand expresses strengh, transforms and creates. I’m thinking of the sea, of its fearsome destructive and its life-giving powers. Thus the hand can both create and destroy. Measure and form must direct the force which, in itself, is neiter good or bad. It is just vitally necessary for life.

(…)

The figures I cut in gold today return after many years and the question remains the same. Where ist Abel, thy brother? The second movement of the Beethoven Sonata Op. 111 sounds like a heart-wrenching question. The theme of the sonate is repeated several times with its ‘extraordinary variations’ and generates harmony, feelings and thoughts. There is no answer but human awareness is growing stronger. In those notes all of life, the quintessential and purest of thoughts, feelings and fate is contained. Is it possible that in the art of jewellery-making something similar happens? That means, in each and every detail that adorns the body and that shows the uniqueness of the person wearing it, the quality of that person, the unseen that denotes that person. As far back as prehistory people were adorning their bodies with precious objects: precious in that these objects transmit values that cannot be expressed in any other wat. They attest man’s wish and ability to change himself and represent the istant in which man has made something sacred, an object that is different from all others. The history of these pieces mirrors the spirit of people: their striving, their wishes, their values. Art is what makes the jewel precious. Wearing these objects means giving shape to an act of optimism, of hope towards life. There were many works, important ones, too, I could not mention. In all of them, however, the striving for knowledge and unterstanding has been expressed more or less clearly. As the serpent says in the bible: ‘Eritis sicut dii (Ye shal be as gods), Scientes Bonum et Malum (knowing good and evil) Et Aperientur Oculi Vestri (and your eyes shal be opened)’. And their eyes were opened. The light represents the revelation of the truth while the eye is a symbol of knowledge. ‘Oculi mentis – the Mind’s Eye’ (Dante, De Monarchia).

(…)

I have spoken about the soul, about beauty and about form: these are words that unite us. I quote from Shelley: ‘A single word even may be a spark of inextinguishable thought.“ A conductor once said to me what we can do today is ‘keep a small flame burning and pass it on to others.’ We are losing our memory, not just the culture of classical antiquity but our entire past. We must regain a silence that will give back an ability to listen and to observe. I believe my work is both the confession and the invitation to stop and pause, to dwell on an object, proud to think to understand and to listen together.

I would like to thank Bruno Martinazzi’s widow, Carla Gallo Barbisio, Ellen Maurer-Zilioli, Karl Bollmann and Arnoldsche Art Publishers for agreeing to print only parts of the lecture reproduced here, which was first published in full in:

Ellen Maurer Zilioli / Karl Bollmann, Bruno Martinazzi, L’Oro E La Pietra, Stuttgart 2007, pp. 6-41.

The article was first published in Art Aurea.