4 Museums – 1 Modernism

New Aesthetics

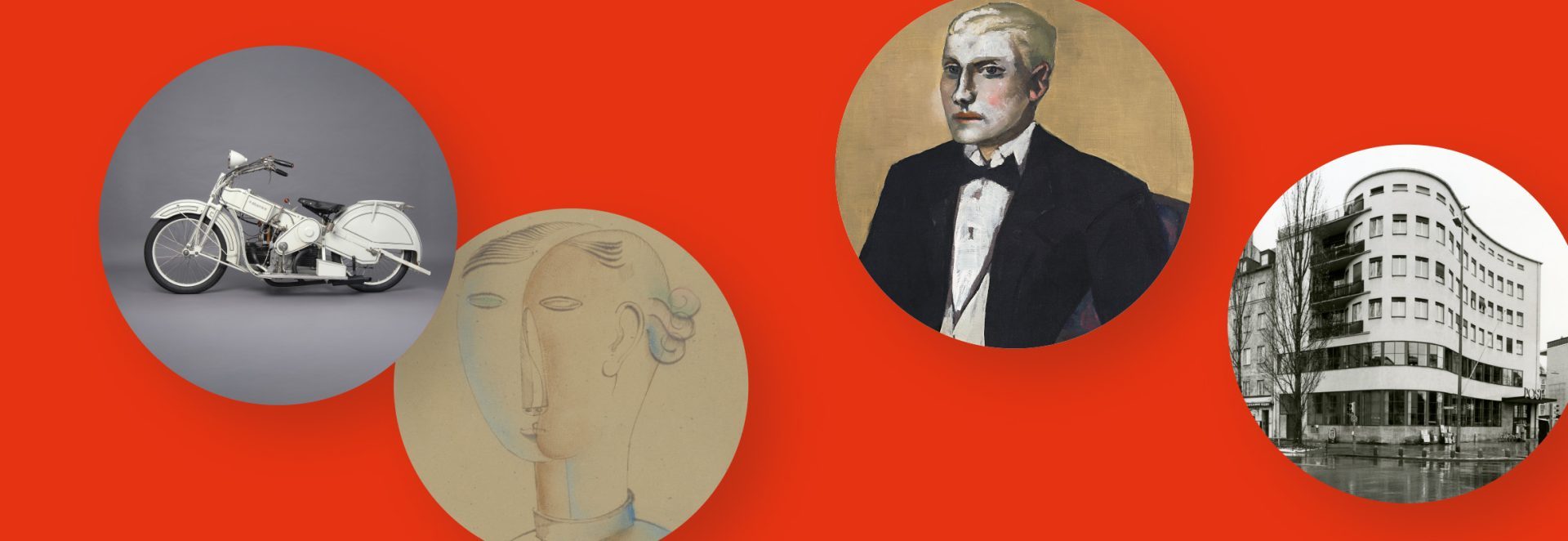

The aesthetics of modernism were characterized by a far-reaching departure from traditional design approaches and a turn towards ahistorical, technical principles.

Particulary prevailing were simple geometrical shapes as well as a palette reduced to white, gray, black, and the primary colors. In both two and three dimensions, abstraction was combined with minimalism and elegance.

Constructivist principles entered into design and painting in the form of vigorous lines, bright surfaces divided into rectangles or triangles, or in graphic designs with differently sized rectangular color fields, often superimposed on one another.

The reduction to geometric shapes also defined “New Building”. White, cube-shaped houses with flat roofs, strips of windows, flexible use of living space, and terraces improved the quality of life by bringing air and light into the interiors. One extraordinary example was the world’s first spherical house in Dresden, a steel structure complete with a metallic outer skin.

Movement as a theme in both architecture and design attests to an intoxication with speed that was expressed above all in the wish for personal mobility, such as is embodied by the White Mars motorcycle.

Photographs transformed natural shapes into abstract form and made them appear like massive, expansive sculptures or edifices. The kind of staging used in experimental ad photography became a fundamental feature of photography in the New Objectivity style.

New Materials and Techniques

Modernism as a cosmopolitan movement with an aesthetic and a socio-political agenda also involved a faith in the opportunities afforded by machines and industrial technology. The wish for transparency, for air, light and opening, but also the need for hygiene, led to trailblazing innovations in architecture and design. At the same time, art and graphic design freed themselves further from old constraints and restrictions, breaking with outdated shapes and structures.

Innovative buildings made of iron, reinforced concrete, and glass were constructed. Tubular steel, aluminum, and molded plywood revolutionized furniture making, while plastics such as Bakelite formed the casings for new electrical appliances.

Transparency became a theme addressed in sculpture and in painting, and collages and photomontages became established art forms. Photography developed a new aesthetic image vocabulary, helped by smaller, easier-to-handle cameras. Artists rediscovered collotypes. Radio, film, and cinema dominated entertainment.

Industrial mass production, standardization, and electrification contrasted with artisanal manufacture and with artistic production. “Progress through technology” was the motto.

New Institutions

Institutions in their roles as teaching facilities, clients, and presentation venues played a decisive part in the development and dissemination of Modernism. In 1919, the Bauhaus was established in Weimar. It relocated to Dessau in 1925 and emerged as a laboratory and stage for new ideas and modes of design with an influence far beyond the region. Architecture, the visual arts, and design were to be consistently aligned to contemporary requirements.

Nevertheless, architecture was not actually taught at the Bauhaus until 1927. By contrast, key advances in “New Building” took place in private architecture practices and in the municipal building offices in Frankfurt/Main, Berlin, and Hamburg, as well as in the Bavarian Post Office’s Building Administration.

Another center of contemporary design arose in the form of the Kunstgewerbeschule (applied arts college) in Halle, founded in 1922 at Burg Giebichenstein. The college set up a specialist photography class in 1927, preceding the Bauhaus in doing so.

The works of Modernist artists and designers were presented to the general public not least by museum institutions, such as the standalone Department of Applied Arts set up in 1925 at Bayerisches Nationalmuseum as Die Neue Sammlung.

New Society

As a result of the experiences gained in World War I and its aftermath, in the eyes of the avant-garde it seemed possible to fundamentally transform the world. Manifestoes by various groups of artists addressed the idea of a “new human” and a new society.

The ideal of the modern person and a socio-critical analysis thereof formed the two opposing poles of art and photography at the time. The search of an idealized image of humanity reduced to basic shapes contrasted with a sober, objective view of reality. This includes the depictions of war-wounded men and women who sought new freedoms and self-determination.

During the Weimar Republic, the creation of housing was considered a governmental task. The new social building tasks included housing estates, recreation homes, and apartments for the unmarried. Social furniture programs were devised for the interiors in an effort to provide inexpensive, durable, and flexible furniture. In turn, exclusive furniture was created in the style of the pioneering high-rise buildings in the USA.

The effects of a lost war, of the Great Depression, and of the emergence of political extremes all posed a major social challenge in Germany. In the final instance, these internal fault lines were what fueled the success of the Nazis, who made aesthetic use of Modernism for its ideology wherever it seemed of use to them.